43, 45 Goodramgate

Tudor townhouses: home to bakers, loved by artists with an 18th century ghost

There are few buildings that can claim to be the Cinderella of York’s ancient past, but this complex certainly qualifies.

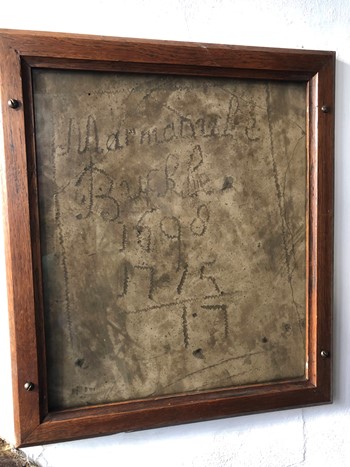

Five street facing bays, with a central passage separating no. 45 from no. 43, form part of two Tudor townhouses built in around 1490. With a colourful history of multiple use, one fascinating feature is the graffiti left by Marmaduke Buckle (1697-1715). Marmaduke had a short but tragic life. Apparently, severely handicapped, he was often accused by locals of practising witchcraft. The torment was too much and aged only 18, Marmaduke recorded the dates of his birth and death on a first floor wall (now protected behind a Perspex panel), before hanging himself from a ceiling beam. His ghost is said to still haunt the building.

For many years, a shambolic wreck of a building in danger of falling down, in the 1800s no. 43 was given a brick frontage and appears separate from the larger no. 45. This Tudor complex appealed to the romantic sensibilities of many artists, including Henry Cave (1810), John Harper (1832), George Nicolson (1837), John England Jefferson (1886), William Boddy (1901) and Thomas Guy (1910). Enter Cuthbert Morrell in 1926, determined to prove that all buildings, and this one in particular, could be saved.

Cuthbert instigated a restoration programme under the supervision of York’s foremost architects at the time, Brierley and Rutherford. Possibly viewed in today’s terms as excessive, their work did rescue the building, making it fit for purpose for the 20th century.

On the outside they removed the external rendering, made repairs to the timber, replaced most of the windows and inserted dormers in the roof to give the impression of useable attic spaces. They also closed the through passageway, converting it into the main entrance.

This passage had been one of the more distinctive features of the building at street level. Its doorway, with its bold cheeks on either side, had a large plank door mounted on massive iron hinges and a small wicket door cut into the timber - see Henry Cave’s engraving. A curious feature for a domestic properly, these large doors with smaller ones cut into them were usually only seen on larger institutional buildings, where individuals could come and go at odd hours without the need to open the large main front door. The answer might be that the passageway not only gave access to the yard behind, but also extended beyond into the Bedern area.

Bedern Hall was the home for the Vicars Choral, who also doubled up as Chantry Priests, earning their money by saying prayers for the wealthy dead to aid them on their journey through purgatory. The cycle of services at the Cathedral, often 10 times a day, would require lots of coming and going and necessitate the need for such a small wicket gate.

Another interesting feature, seen on early paintings and engravings, was what appears to be a loading bay at second floor level above the street. A Dutch, or half-timbered door, can be seen, although no hoist is visible. Over the years many of the occupants were bakers and high level storage, away from rats and other vermin, would be an essential requirement.

In 1890 the site of no. 45 was offered for sale:

“… being freehold shop and dwelling house, in the occupation of Mr Pool grocer, together with bakeries, stables, out buildings, yard and three cottages behind the same.”

Any horses stabled here would almost certainly need to quite small; at least less than 16 hands, to negotiate the doorway and passage!

Back to the 1926 restoration and on the inside Brierley and Rutherford heavily reconfigured the layout, taking away all earlier staircases, much of the ground floor studwork and all fittings original to the building. The result was the re-imagining of a small open hall rising through all floors to an open attic. A postcard from around 1950 shows an impressive space being used by the Minster Café. The rooms on the first floor, although heavily restored in the 1920s, do retain many interesting features and little has changed since then.

The most recent discovery, made during renovations to the attic and roof space, has been a pewter plate and mummified cat. Found against one of the roof beams, talismans to ward off 'evil spirits', cat’s have often been found tucked away in building structures like walls and floors, a practice that may have come to us via the Romans. We’re not quite so sure about the plate. Thankfully, examinations of other sites conclude that cats were not walled up alive, but would have been already dead before being hidden.

Today, no. 43 is a shop and no. 45 Goodramgate is occupied by the Italian restaurant La Piazza Antica.

Discover more about no. 43, 45 Goodramgate

43, 45 Goodramgate

York

YO1 7LS

Historic England Grade l listed buildings

Why is 45 Goodramgate significant?

Three-storeys tall with jetties at both first and second floors, and doubled curved wind braces, No.45 Goodramgate is one of the most impressive timber-framed buildings in York.

The site is actually an amalgamation of three timber framed ranges, dating from the late medieval and post medieval period. This front timber-framed range was built as five bays with a central passage, of which no. 45 represents the southern half and passageway. The northern portion of the frame survives behind a later brick facade as nos. 41 and 43 Goodramgate. The ground floor was heavily altered in the 18th and 19th centuries when the site housed a large bakery and grocers.

The building today is the result of a careful restoration in 1929 by prominent architects, Brierley and Rutherford. Together with its neighbours, no. 45 Goodramgate forms part of the largest surviving run of exposed vernacular timber framing in the city. The site also represents an important early example of vernacular architecture restoration in the city, and by a major architectural practice.