23 Stonegate

Unique and beautiful: Roman roots, a medical history and hidden garden

Medieval properties in York have a habit of keeping secrets and no. 23 Stonegate is no exception.

Accessed off the ancient street of Stonegate, no. 23 Stonegate is found at the end of an enclosed alleyway below flying freeholds - where neighbouring properties overhang another. The passage would originally have led into an open courtyard, sadly now lost by encroaching neighbours. You are welcomed to the building by a pair of fielded six panelled doors with three-pane borrowed lights above. Look closely and you’ll notice the remains of an 18th century Sun Insurance fire mark set high up between the doors behind the large lantern. There is also a lead rainwater hopper displaying the date 1590. A unique example in York and, possibly, one of the earliest dated rainwater hoppers in the UK.

The whole property was originally built as two, or even three houses, each with a large ground floor room and first floor chambers open to steeply pitched roofs. Second floors were added later, forming attics with the first floor ceilings decorated with ribbing and panelling.

On entering the property you’ll get a sense of the complexity of this beautiful old building. Immediately on your left is a low narrow wing, known in early deeds as Little Paradise, it has a fine medieval fireplace acquired from a nearby house and a handsome balustraded staircase leading to the upper floors.

The tall projecting wing on the east, it’s thought, could have been part of the medieval Barley Hall next door. The steep attic space is accessed through a sliding The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe style doorway and has remnants of 19th century strapwork design wallpaper pasted to the partition boards.

On the outside you’ll see two gabled centre blocks, one with a jettied first floor and both facing onto the charming walled garden. The blocks have a complex arrangement of rooms that have been adapted over time and not all the changes are yet fully understood.

In 1804 Mr Henry Anderson acquired both buildings, together with land to the west owned by the Bishop of Chester. However, it was his son Dr. William Anderson who made significant changes and further acquisitions from the 1830s onwards.

In the centre section William added a stone staircase with impressive iron balusters, probably supplied by the Walker foundry of York, ornamented with bound serpents, the symbol and badge of Aesculapius, the ancient Greek father of medicine. It is worth noting that York’s Walker foundry designed and supplied the hugely impressive gates and railings for the British Museum. The ground floor rooms at no. 23 were used as a dispensary and medical consulting rooms.

This main ground floor room on the north front is now oak-panelled, but this cladding may have been added during restoration work in the 1970s; adapting sections rescued from the Plumbers Arms in Skeldergate, a building demolished in 1965. On the adjoining elevation outside, the plaster was stripped away to reveal the half-timbering and all the missing windows were replaced with metal framed Crittal windows.

William’s son Tempest Anderson, another doctor and perhaps best known for his research on volcanoes, made the last major changes. In 1870 he commissioned the building of the large west wing as a guest suite.

The large ornate dining room on the ground floor was created and decorated with Grecian frieze motifs and a complex ceiling rose. The motifs are taken from Owen Jones’s Dictionary of Ornament written in 1858. Jones had come to York at this time to advise on the redecoration of the Assembly Rooms in Blake Street and may well have been consulted by Tempest.

The doors, although mostly painted over, are made from an exotic blend of Satinwood and Rosewood timbers. The evidence of which, is revealed on the inside of a space now used as a glass cupboard. There also has a handsome black basalt fireplace similar to the designs of Thomas Hope. On the first floor there were bedroom suites for the guests and a ballroom created on the second.

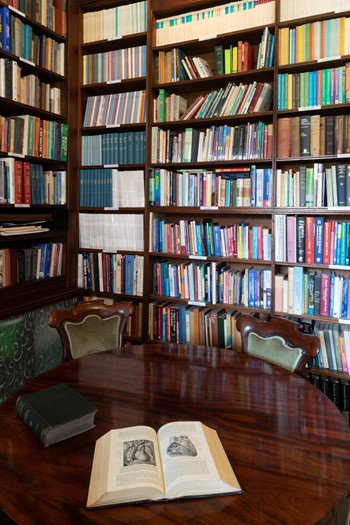

Today, home of the York Medical Society since 1915, the dining room is used as a meeting and lecture space for the organisation. Founded in 1832, the Society had no permanent home until it acquired the buildings from the Anderson family in 1944. The Society undertook a thorough restoration in the 1970s under the supervision of Harrogate architect practice Taylor, Bown and Miller, led by John Miller. At this time the upper floors were re-ordered to create seven self-contained flats, most with views over the garden.

The landscaped garden is another York hidden treasure. The bare outline, as we see it today, is recorded in the 1851 Ordinance Survey map of York, but the present raised terrace and mature planting creates a charming and elegant design. Two large Mulberry trees have sadly been lost, as has a huge London Plain tree, but what remains is a sophisticated medley of colour and structure. It has been suggested that John Miller was involved in the early layout of the RHS Harlow Carr garden near Harrogate. This may go some way to explaining Millar’s involvement and why a York architectural practice was not employed in the 1970s restoration.

Intriguingly, showing much earlier habitation, archaeologist and historian Peter Wendham discovered fragments of Roman tiles dating from the 1st century AD, whilst excavating the basement in the 1970s. At this time the Legio VII legion were stationed in York. The find also included coins from the 4th century.

In 2018, York Conservation Trust acquired the site and set up a lease-back arrangement with the York Medical Society, thus ensuring its long-term future and the enduring preservation of this wonderful medieval and Victorian building complex.

Discover more about 23 Stonegate

23 Stonegate

York

YO1 5AW

Historic England Grade ll* listed building